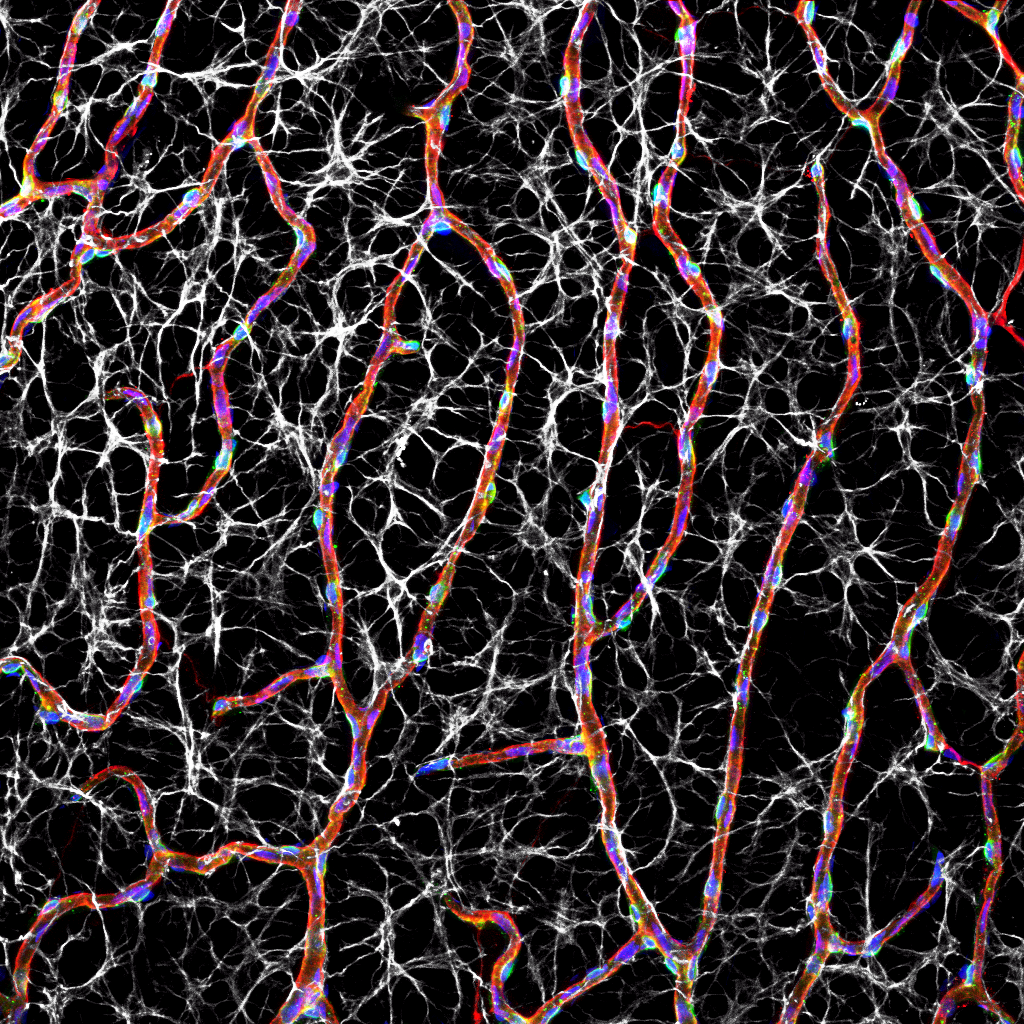

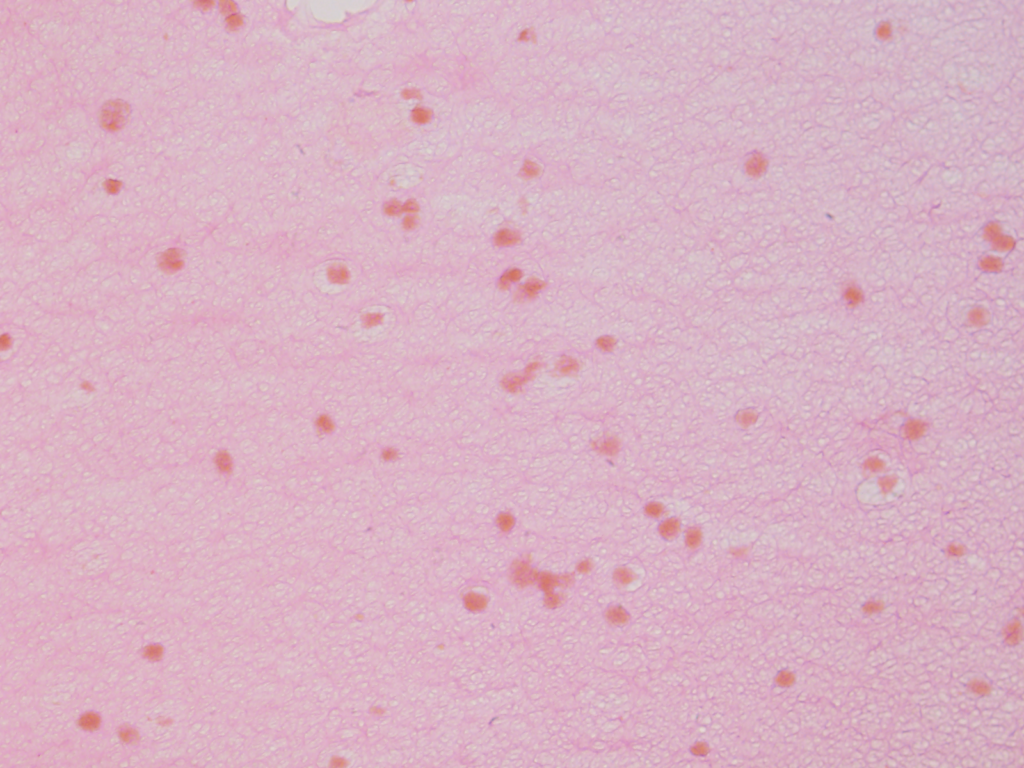

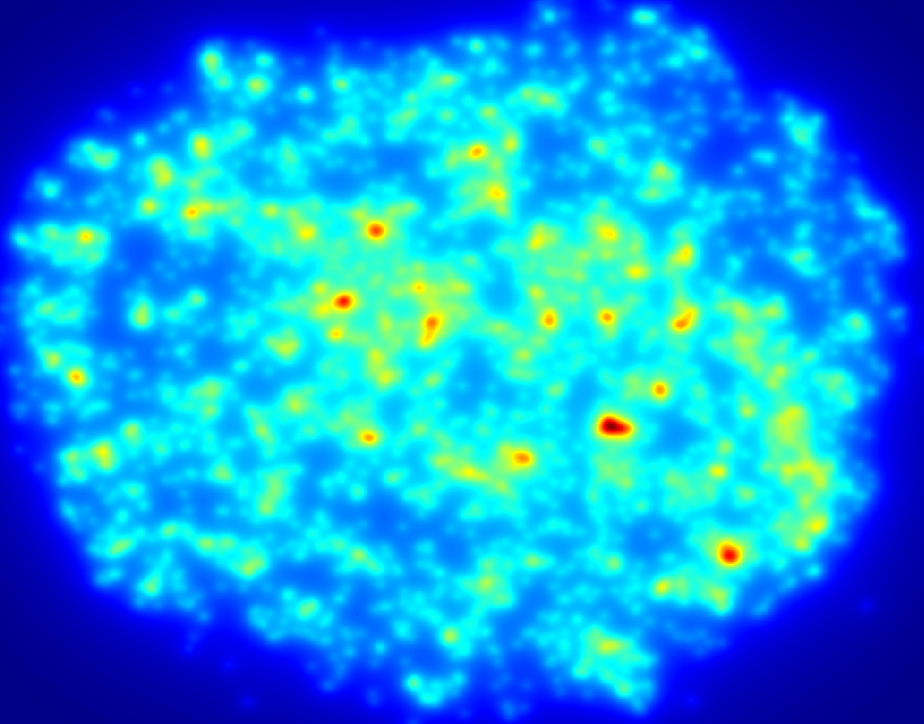

Northern slope of Mt. St. Helens.

Northern slope of Mt. St. Helens.

Volcanic 50 is a 50km ultra trail race, organized by Go Beyond Racing that circumnavigates beautiful Mt. St. Helens. I choose this event to enjoy a race outside of California, and experience a unique course leading up to Mountain Lakes 100 in late September. Heading into the event I felt fit and healthy, I was thoroughly enjoying spending time on the trails with friends and my training had been progressing injury-free. After spending a few recreational days exploring Echo Lake I took a short Thursday evening flight from San Francisco to Portland where I picked up my rental car and drove an hour to my hotel for the night. On Friday, the day before Volcanic 50, I arrived at the event site located at Marble Mountain with plenty of time to relax and take in the scenery before Saturday’s race.

Race day started out well, after checking in at 530am I ate a small breakfast and finished preparing for the event, eventually walking over with the masses to the starting coral at 645am for the race directors pre-race instructions and well-wishes. The race started out on a relatively short 2,000 ft climb that covered miles 0 to 4, after-which the course leveled out and traversed a boulder field that at first was an amusing novelty, however, later became a complete nightmare. During this initial climb up to Loowit trail we were afforded brief views of the volcano through trees as we arrived at mile 4 and the first aid station. Here, I quickly ate PB&J sandwiches and S-caps to help blunt what was forecasted to be a toasty day. After leaving the aid station in good spirits I made my way towards aid station 2, positioned 8 miles away.

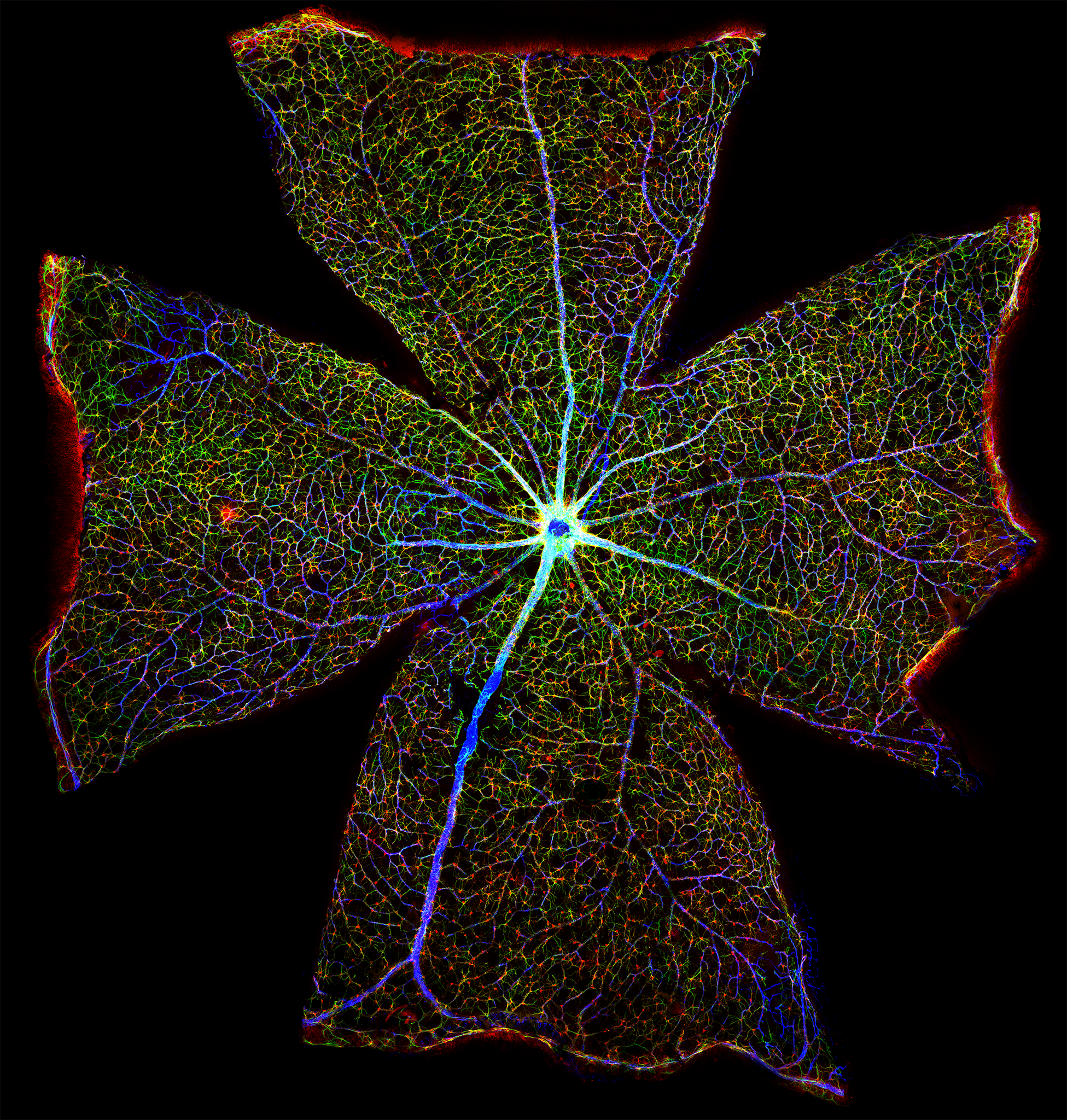

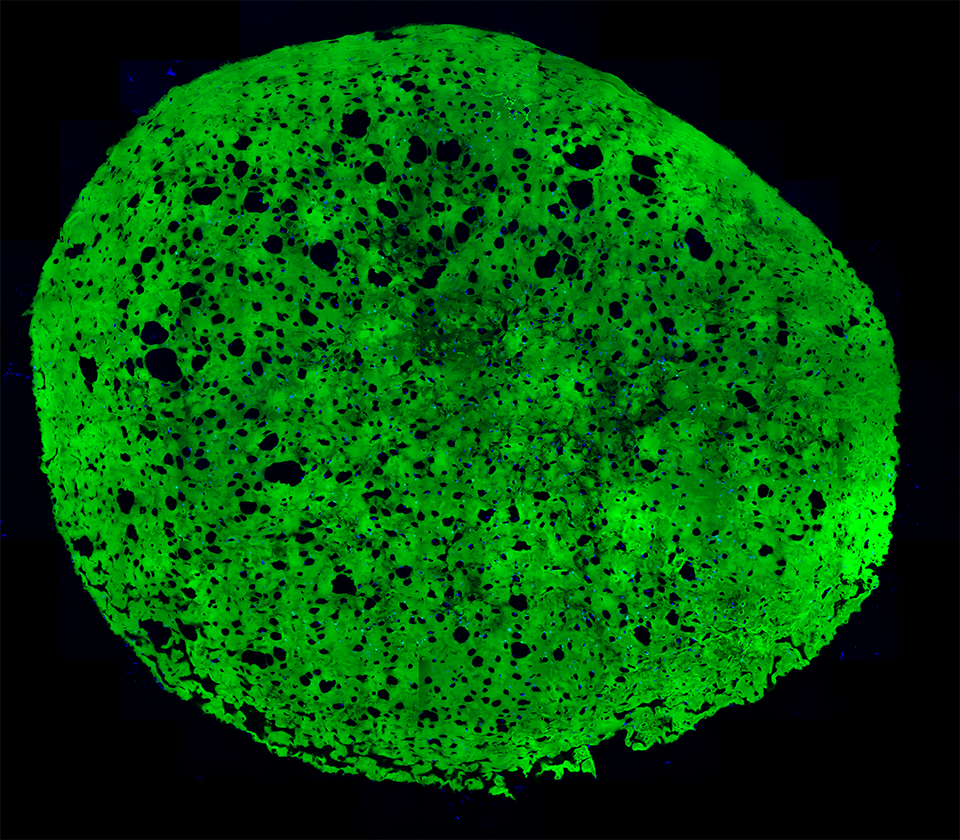

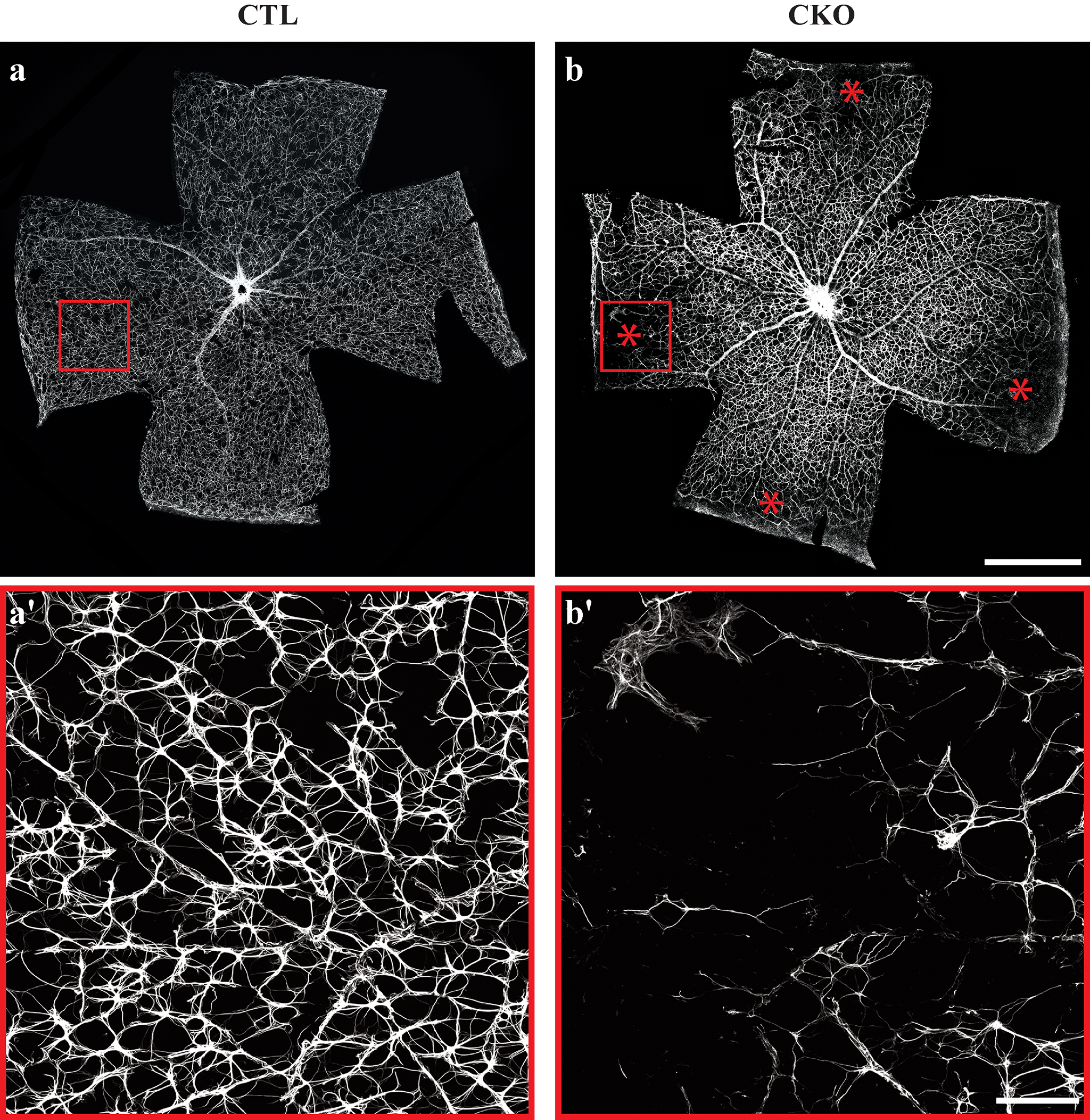

Southern slope of Mt. St. Helens.

Southern slope of Mt. St. Helens.

The course between aid station 1 and 2 was deceptively smooth and tranquil, by this time the traffic jam at the start had thinned out, and the elevation profile was relatively flat or downhill. In retrospect, I wish I had slowed down, but thought, its 32 miles, that’s just a sizable training run, I can floor it (relatively speaking) while its still cool, and so I did. We wound our way through miles of forested terrain until arriving at aid station 2, 12 miles into the race. Here, I ate more of the usual aid station foods, thanked the wonderful volunteers and headed out towards aid station 3, 8.2 miles away. Little did I know that immediately after leaving aid station 2 the true difficulty of course would begin to reveal itself. Less than 100 yards away from aid station 2, we headed down a rather large, gravel filled ravine that required both a water crossing and the use of anchored ropes to descend and ascend. I dreaded getting my shoes soaked and then having to continue to run across rugged volcanic terrain. Once we emerged from the ravine we climbed over the next 2 miles on loose, sandy terrain that was only about a foot and a quarter wide alongside a rather steep embankment. This was probably the most memorable part of the race as we became up close and personal with the beginnings of the northern slope of Mt. St. Helens (the side reorganized in the massive 1980 eruption). After reaching the northern slope of the volcano temperatures noticeably began to rise as the course guided us across the barren side Mt. St. Helens.

Mt. St. Helens from Lahar lookout point.

Mt. St. Helens from Lahar lookout point.

The northern side of Mt. St. Helens still bears geological scars that continue to dominate the landscape, the scene was so spectacular that I stopped several times to appreciate the magnitude of what happened on May 18th, 1980. The scope of damaged landscape from the powerful pyroclastic flow were clearly evident as the entire northern slope of the mountain was ripped open by the blast. On this day, large waterfalls rushed millions of gallons of snowmelt off the north face and venting volcanic gases filled the distant air from a very active and growing lava dome. Back to the race, as I trekked across the north side of the mountain the course traversed what looked like the surface of the moon, gentle rolling hills became increasingly challenging under the brutal 93 degree sun.

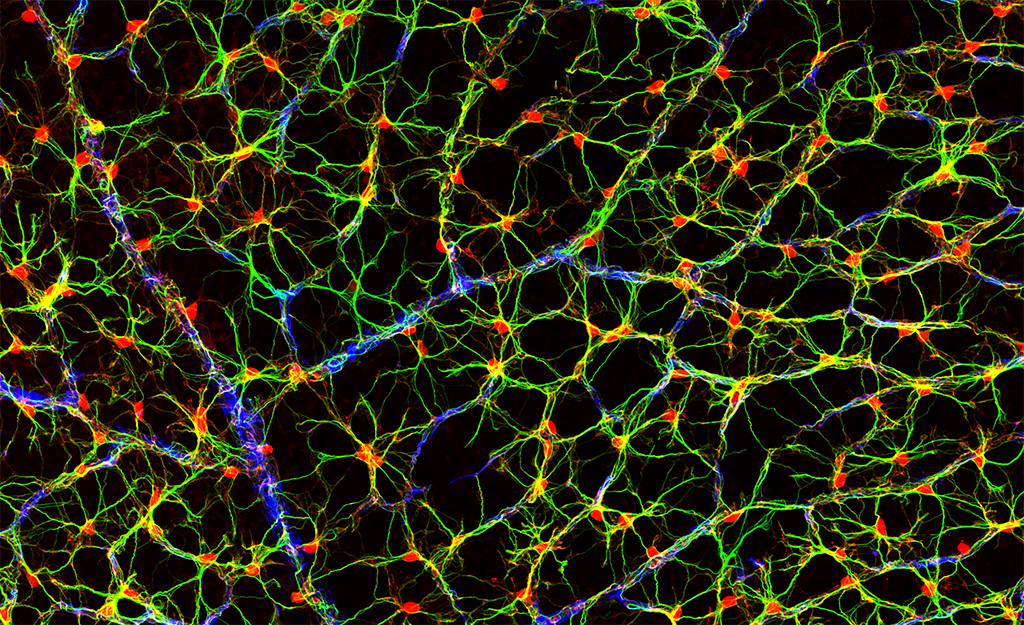

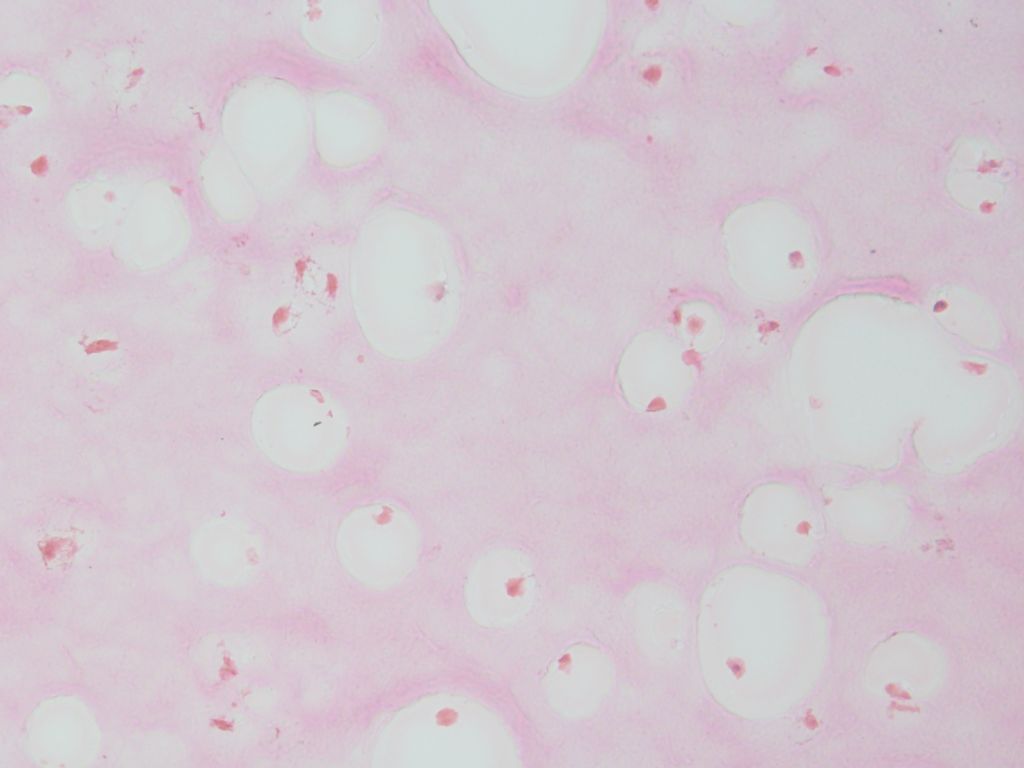

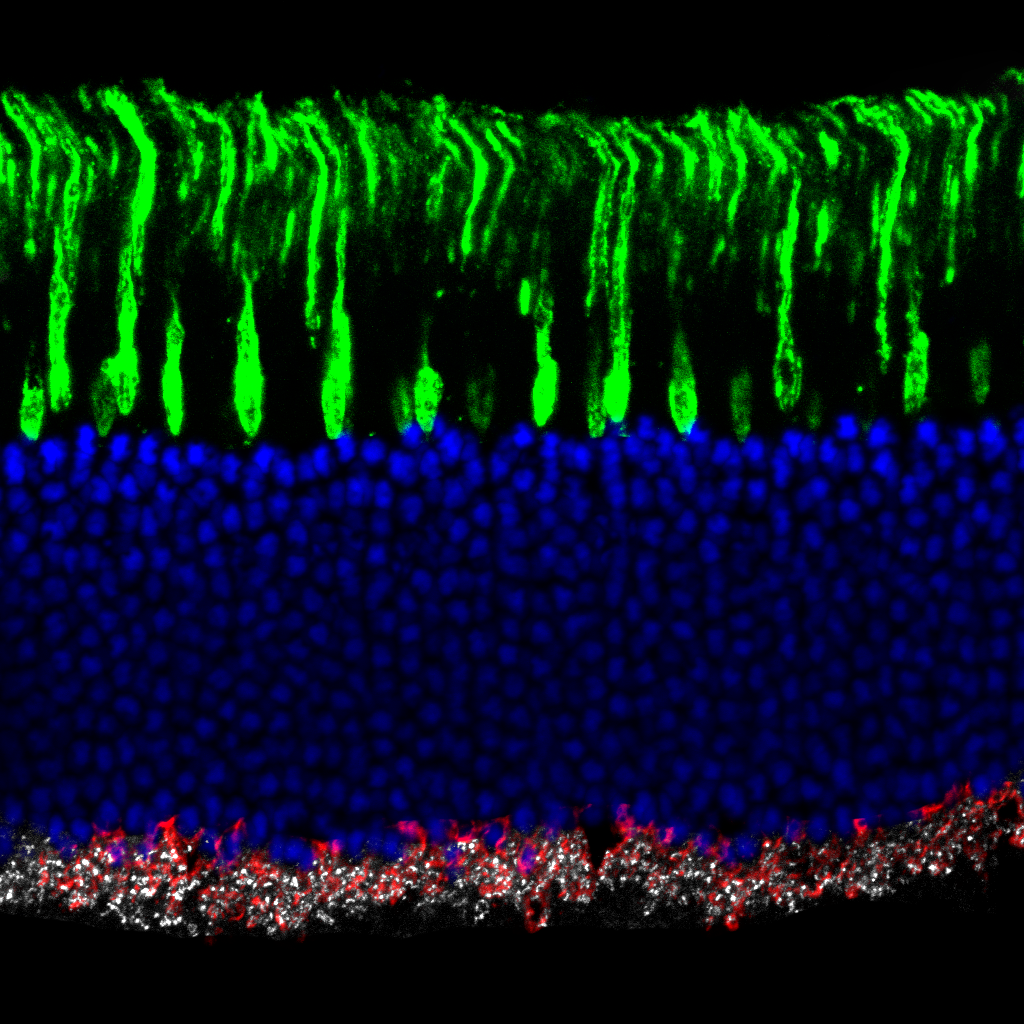

Nearing the spring of life aid station.

Nearing the spring of life aid station.

A swath of green in a landscape of brown as a result of rushing spring water.

A swath of green in a landscape of brown as a result of rushing spring water.

At this juncture, I was a hair under halfway through the course, yet I began to accept that I was in for a long and difficult day. The last two miles to aid station 3 were especially quite miserable as a result of dehydration and caloric depletion. Indeed, three miles after leaving aid station 2, I had ran out of water, making the remaining 5.2 miles to the aid station 3 an eternity, however, through tough love and encouraging words from fellow runners I arrived at aid station 3, “the spring of life.” The supplies here were minimal as we were advised during the pre-race instructions, but still very much appreciated. This aid station was staffed by NASA suited volunteers equipped with water pitchers that collected the most glorious natural spring water on the planet. After was seemed liked never ending miles in the heat the feeling of being doused with refreshing, ice-cold water slowly began to revitalize me as I uncomfortably swallowed more S-caps and trail butter.

Aid station 3, “the spring of life” and NASA-certified bros.

Aid station 3, “the spring of life” and NASA-certified bros.

Psychologically, seeing runners arrive at this oasis was comforting, it served as a critical reminder that I was not alone, this was a difficult course on a difficult day. I watched runners arrive for several minutes as I continued to sit quietly on a volcanic rock (there are millions on this course) waiting to recoup enough energy to begin the trek to the next and final aid station. I also took a few extra minutes before leaving and untied my shoes to examine my feet, shaking out the sand and rocks that had accumulated. Lastly, before leaving the spring of life, I topped off my water supply and slowly began to shuffle my way towards aid station 4, located 3.4 miles away. It wasn’t far before I hit the proverbial wall a second time. Luckily, I came across two wonderful race photographers who were kind enough to offer words of encouragement at a difficult time mentally. As I hunched over seeking a moment of reprieve I recall uttering fragments of incoherent sentences as they continued to photograph the scenery and other runners. I distinctly recall one of the photographers saying, “we’ve so been there! are you questioning your life decisions right about now?” I thought, how can she hear my thoughts? While I was trying to catch my breath, I had a direct line of sight to the next climb that needed to be negotiated in order get to the last aid station, the sight alone elicited a strong urge to let out a loud profanity-laced scream, but there were other individuals on the course struggling as I was, thus I opted against adding to what felt like humiliation. As I unwillingly shuffled my feet on the trail heading towards the climb I said to the photographers, “I don’t know how I’m going to get over that ridge” and one replied, “you don’t know how, but you will.”

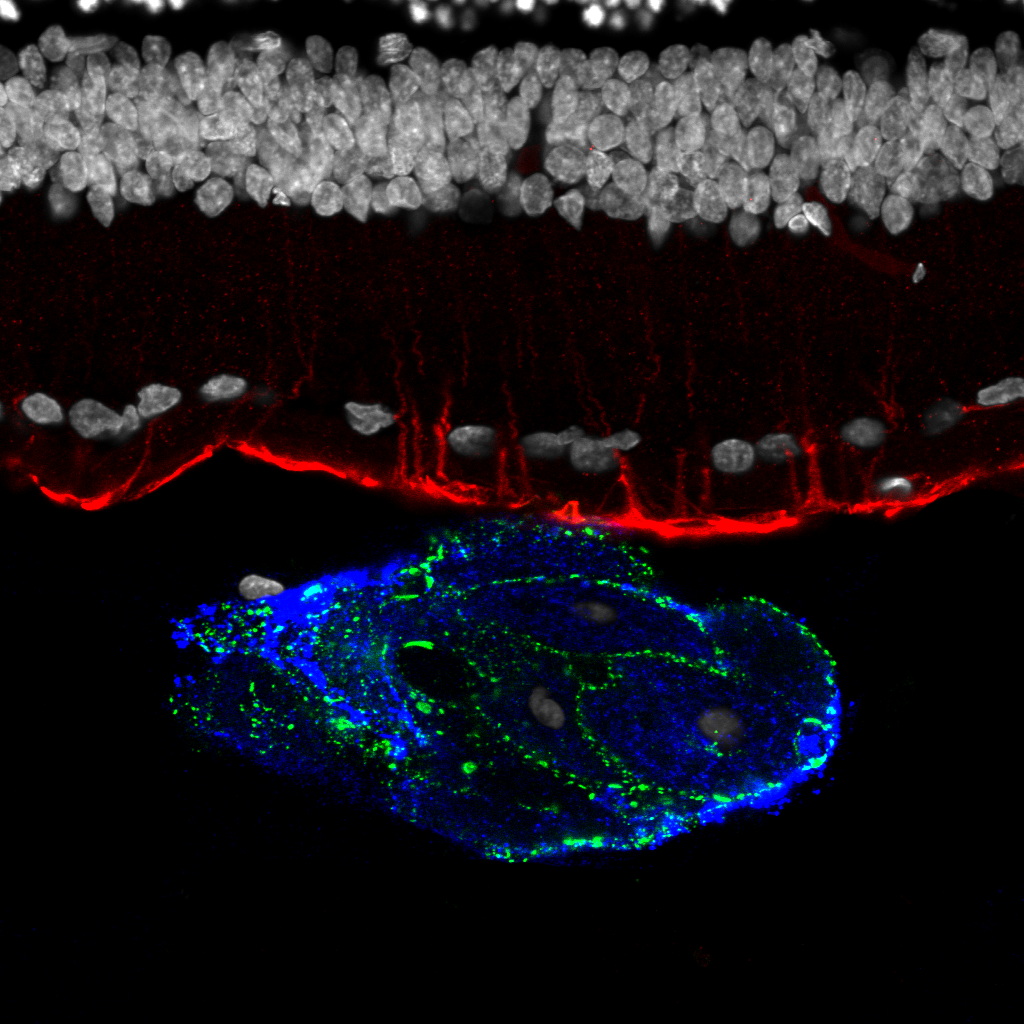

Heading towards the final aid station.

Heading towards the final aid station.

Slowly but surely I made my way up through the switchbacks eventually summiting the ridge, gasping for oxygen in the suffocating heat. When I reached the summit, I looked back down towards the photographers who had turned into small dots on the landscape with a sense of elation, although I had no idea how I was going to get over that ridge under the circumstances I somehow managed to, and I thank them for it. Heading down the ridge offered more rocky unstable terrain, endless ups and downs came and went, but my confidence began turn around on an emotional rollercoaster of a day. Finally, after hours of desert-like heat and negative thinking that, “this is going to be my first DNF,” I made it to the last aid station and only cutoff, well ahead of the 4pm deadline. Here, I spent extra time in the shaded tent savoring several delicious pickles, PB&J sandwiches, oranges, Pringles, and more S-caps. Finally, after eating and waiting for my heart rate to slow down, I decided it was time to tackle the last 8.5 miles and left aid station 4 on my way towards a difficult finish.

The last 8 miles of the race were nothing short of a mental slugfest. The last section of Volcanic 50 offered up two very challenging features, one was the seemingly excessive amounts of lahars that had to be traversed, these constant ups and downs appeared to keep runners from finding any sort of rhythm. Under different circumstances these lahars wouldn’t have caused concern, however, on this day, at this juncture they proved to be problematic. Rocky, unstable sections became increasingly difficult to navigate. I remember constantly looking towards Mt. St. Helens for feedback, noting familiar features that let me know I was nearing the finish line. The second challenging feature was an almost mile long ankle-snapping boulder field that we were warned about during the pre-race instructions. However, after the boulder field it was simply a left turn and downhill for 1.5 miles to the finish line on a smooth trail under the cover of shade. Unfortunately, about 300 yards away from the infamous, “left-turn” I lost my hearing and began to experience blurred vision. I was aware that my body was physiologically shutting down, so I sat down on a very uncomfortable volcanic rock that was close enough to see the turn downhill and began to dry heave. Two women, who were out hiking were kind enough to talk sense into me about taking my time finishing. I slowly drank more water and electrolytes, forcefully ate small salted potatoes (thank you runner kind enough to share) and waited in the shadows of the rock until my muscles somewhat stopped cramping before I proceeded to cross the remaining boulder field to the left turn. I ended up crossing the finish line 12 hours after I begun, in a race that packed over 7,000 of elevation gain in 32 miles on a course that simultaneously humbled and inspired me.

Volcanic 50 turned out to be a unique experience on a historical site that offered spectacular views of other stratovolcanoes on the Cascade Range, namely Mt. Rainier, Mt. Adams, Mt. Jefferson, and Mt. Hood. Symbolically, on land that was obliterated decades ago, new signs of life were emerging, small tree shrubs and wildflowers now dot a landscape that was once strangulated by volcanic debris, much like individuals who struggled through the 2017 edition of Volcanic 50.

Lastly, a very heartfelt thank you to all the volunteers who were gracious enough be out in the elements for hours on end in order to support all the runners. The photographers for helping to capturing the journey and of course the race directors who organized and executed a one of a kind race.

Renee Seker, race director.

Renee Seker, race director.

Northern slope of Mt. St. Helens.

Northern slope of Mt. St. Helens. Southern slope of Mt. St. Helens.

Southern slope of Mt. St. Helens. Mt. St. Helens from Lahar lookout point.

Mt. St. Helens from Lahar lookout point. Nearing the spring of life aid station.

Nearing the spring of life aid station. A swath of green in a landscape of brown as a result of rushing spring water.

A swath of green in a landscape of brown as a result of rushing spring water. Aid station 3, “the spring of life” and NASA-certified bros.

Aid station 3, “the spring of life” and NASA-certified bros. Heading towards the final aid station.

Heading towards the final aid station. Renee Seker, race director.

Renee Seker, race director. Echo Lake via picture point.

Echo Lake via picture point. Ralston peak; elevation 9,300ft.

Ralston peak; elevation 9,300ft. Heading towards Triangle Lake.

Heading towards Triangle Lake. Triangle lake.

Triangle lake. Crystal range towering above Lake Aloha.

Crystal range towering above Lake Aloha. Sign posts guiding hikers and backpackers on the PCT.

Sign posts guiding hikers and backpackers on the PCT. Lower Echo Lake.

Lower Echo Lake. Verga seen over lower Echo Lake during a thunder storm.

Verga seen over lower Echo Lake during a thunder storm. Some trees in the area are well over 1,000 years old.

Some trees in the area are well over 1,000 years old. Wind swept pine.

Wind swept pine. Milky Way from lower Echo Lake.

Milky Way from lower Echo Lake.

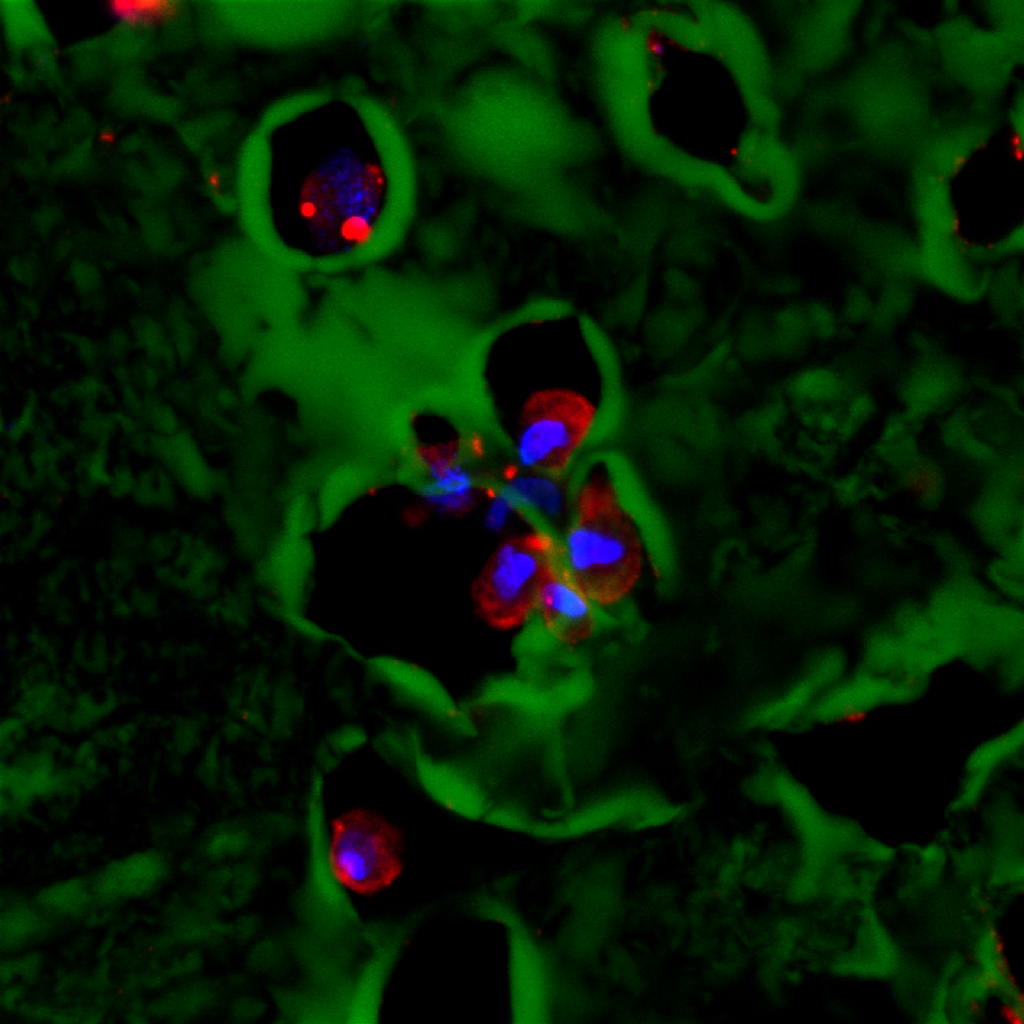

Composite image.

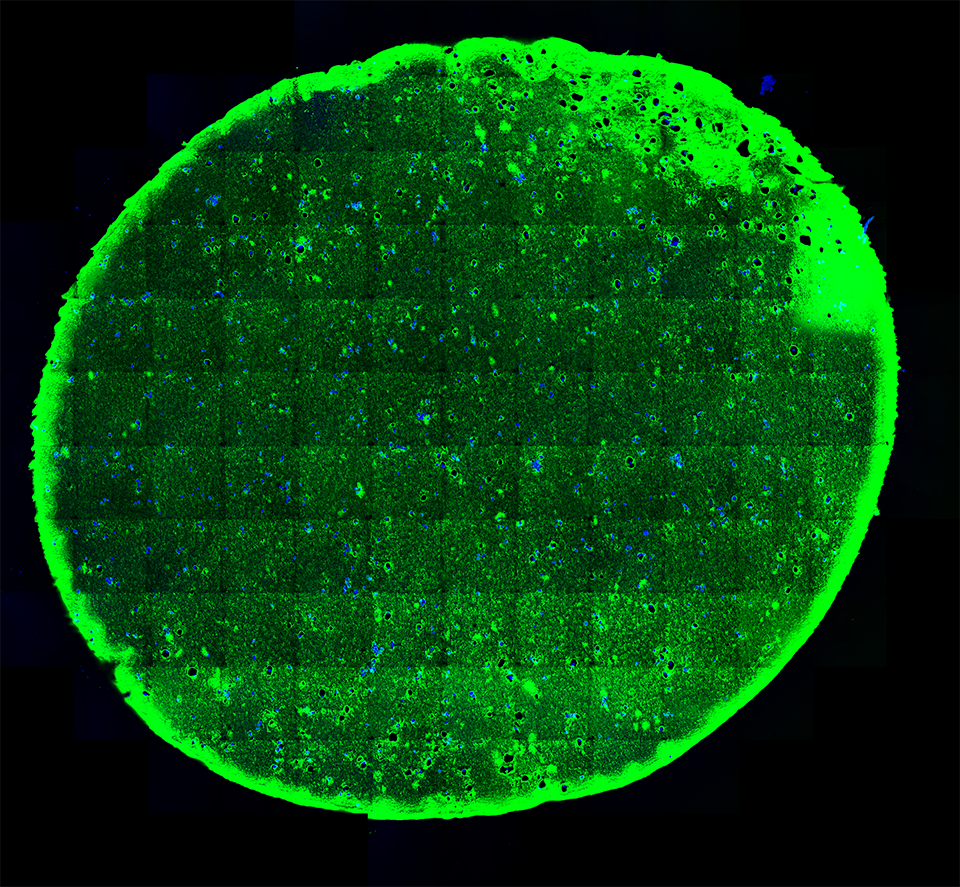

Composite image. Magnified 400 times.

Magnified 400 times. Magnified 600 times.

Magnified 600 times.

Approaching Inspiration Point. Photo:

Approaching Inspiration Point. Photo:  Tunnel trail.

Tunnel trail. Return leg at West-fork Cold Spring/Gibraltar junction. Photo:

Return leg at West-fork Cold Spring/Gibraltar junction. Photo:  Tunnel trail connector, looking towards Inspiration Point. Almost home.

Tunnel trail connector, looking towards Inspiration Point. Almost home.

Race Director: Luis Escobar. Pre-race remarks, “This course is hard as shit, it’s over 11,000 ft of this, and this.”

Race Director: Luis Escobar. Pre-race remarks, “This course is hard as shit, it’s over 11,000 ft of this, and this.” Creator and founder of Santa Barbara Nine Trails: Patsy Dorsey.

Creator and founder of Santa Barbara Nine Trails: Patsy Dorsey.